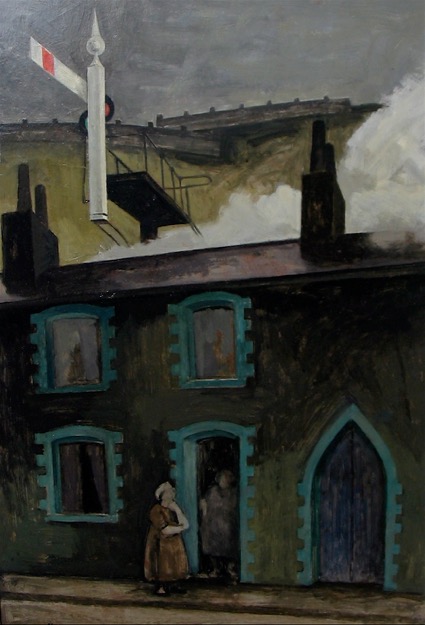

THE SWEEPING CURVE OF TERRACED HOUSES perched on hilltops. Precipitous steps and narrow back alleys. Reflections scribbled on wet slate roofs and rain-soaked tarmacadam. Lampposts, chimneys, television aerials, pollard trees, pithead winding gear and railway signals piercing the skyline. Slagheaps cloaked in dreary rainclouds. Miners changing shift. Old men at gossip. Women shopping and children at play. This was the Rhondda of George Chapman, one of the most remarkable and original British painters of the twentieth century who made a hugely significant contribution to art in Wales as the painter of the south Wales coal-mining valleys.

When Chapman discovered the Rhondda Valley in 1953 at age 47 he was a disillusioned painter who had all but abandoned the search for a subject and means of personal expression through paint. A successful graphic designer working for Shell and London Transport during the 1930s, he had given up commercial art to study painting just before the outbreak of World War II. In 1948 he relocated from London to northwest Essex where he lived at Great Bardfield and became an active member of its thriving artistic community that included Edward Bawden, Michael Rothenstein, Bernard Cheese and John Aldridge. This would be the most productive and rewarding period in his career. After he moved with his wife Kate and their young family in 1960 to a moated house in Norfolk, and four years later to the Georgian seaside town of Aberaeron on the west Wales coast, he missed the Open House exhibitions as well as the friendship and support of like-minded artists.

Kate Chapman gave up a career in art to support her husband and to raise their three children. Born in Norfolk in 1926, Kate (née Ablett) was introduced to Chapman in 1946 at Norwich School of Art where she was a student. They married the following year. Kate painted in the constricted space between family life and her husband’s work. Though she painted portraits of her children and a small number of landscapes, it was fruit and vegetable arrangements that mostly preoccupied her. These apparently simple compositions of fruit, eggs, vegetables, domestic utensils and ornaments are subtle yet complex. What appears at first glance to be a casual juxtaposition of watermelon and knife repays further examination. Kate’s interest in antiques was long standing. In Aberaeron she owned a antique shop where many of her favourite objects found their way into her compositions – a Llanelli plate, Belize porcelain, slag-ware beaker, slipware dish and Victorian glass dome filled with stuffed exotic birds.

George Chapman’s quest for a meaningful subject matter and an idiosyncratic style led him to emulate works by the painters he admired: Daumier, Cézanne, Sickert and artists of the Euston Road school. His study Mr Bone, Butcher of Bardfield tells of his high regard for Chaim Soutine and Georges Rouault, while The Threshing Machine, The Water Bowser and Gors Fach, Pennant see Chapman try his hand at abstraction following a visit to St Ives.

During the 1950s and 60s, Chapman staged critically acclaimed solo exhibitions of his mining subjects in London and Cambridge. His paintings were celebrated amid a growing awareness of and interest in the British working classes, made manifest in the work of the so-called ‘Kitchen Sink’ painters, the ‘Angry Young Men’ of literature, and films such as Tony Richardson’s A Taste of Honey. The contrast between the village of Great Bardfield – a quintessentially English mix of medieval, half-timber, thatch and Georgian red-brick properties surrounded by open pastureland – could hardly have been more stark, physically as well as socially, than with the drab mining communities of close-built terraces dwarfed by heavy industry and chapels, enclosed cheek by jowl in the steep-sided, cloud-shrouded valleys that he painted. The period of success Chapman enjoyed, however, was all too short-lived as critics increasingly engaged in the debate surrounding Abstraction, after the Tate Gallery’s 1956 exhibition of American Abstract Expressionism, and Pop Art following the Whitechapel exhibition This is Tomorrow.

Chapman’s experience working for Frank Pick at London Transport and Jack Beddington at Shell, along with his training at the Slade School of Art and the painting school at the Royal College of Art, are manifest in his paintings. The Steps and A Welsh Village exhibit dynamic compositions, sensuous handling of paint and attest to his well-honed sense of design and pattern. The weather also plays an important role in the visual drama of Chapman’s paintings as dense clouds break, the skies open, and daylight – for it is rarely sunlight – silhouettes slag tips on the skyline and reflects on the wet surfaces.

Chapman depicted the people that inhabit this harsh environment with a genuine affection. Neighbours engaged in Welsh Gossip, colliers After the Shift and pedestrians on A Steep Road are integral to its makeup. The artist quickly realised that the old mines that had first attracted him to the valleys ‘had nothing more to say’ to him. It was then, Chapman told Huw Weldon in 1962, that he began to paint a ‘visual novel of the mining valley concentrated entirely on the life that is going on there and describing everything the people are doing’. He displays a genuine empathy with the miners and a community whose economy was dependent on the resources hundreds of metres below their village. His palette of earth colours – greys, greens, browns and black – evoke the austerity of the coal-mining valleys. The paint he applied in thick impasto, then scraped back and scratched, represents the hard labour of the miner.

Though most closely associated with the Rhondda Valley, Chapman visited communities across the south Wales coalfield in search of interesting subjects that he felt possessed the qualities of a good picture. ‘Out of the squalid, Chapman can squeeze poetry till the pips squeak,’ wrote John Dalton for The Guardian in 1959, ‘for Chapman people are not crowds, swarming like ants, but individuals […] isolated, purposeful, looking as though they will be the last pedestrians in the world’. ‘If it’s drawing you’re after,’ he added, ‘George Chapman is your man’.

After his move to Great Bardfield, Chapman took up printmaking. On Michael Rothenstein’s press he made his first etchings: Essex Farm at Great Bardfield; Pennant in Cardiganshire where his friends kept a cottage named ‘Gors Fach’; Kate pregnant with their first child; and House on Rocks near Aberfan in south Wales. Rothenstein was a printmaker hugely experienced in relief, intaglio and monotype techniques. While he claimed that he did not teach Chapman, the prints suggest that Rothenstein’s creative processes had rubbed off. House on Rocks, for example, is experimental and inventive in its combination of intaglio processes – soft ground, aquatint and burnishing – and is simplified almost to abstraction. Etching clearly fulfilled Chapman’s graphic needs.

A growing confidence led him to develop etched subjects on a larger scale. Chapman bought a large-bed press that was one of three made for the Great Exhibition in 1851. He drew outdoors directly on to the zinc plate tacked to a board and secured with strap around his neck, or propped on the steering wheel of his car. Imaginative explorations of etching processes gradually gave way to more conventional methods for a series of striking architectural compositions using deeply bitten line and coarse grain aquatint. Commissioned in 1960 by Robert Erskine for St George’s Gallery, the ‘Rhondda Suite’ etchings record a particular place and time: The First Building shows a ‘bubble car’ drive past the first gents public lavatory on entering the lower Rhondda Valley at Trehafod, while Pigeon Huts depicts coops near the Lewis-Merthyr Colliery.

After the Shift and Slagheap Railway, painted some time between 1962 and 1965, signal Chapman’s endeavour to devise a painterly language that approximated the optical effects of the human eye. With his gaze fixed on a point in the distance, it took some time before he was aware of other objects around him. In his statement for a 1962 solo exhibition at the Zwemmer Gallery, he explained ‘there would be areas of full reality against areas of near or complete abstraction where the colour, tone and definition would naturally recede’. His ‘sense of space’ also changed as the objects on which he focussed appeared closer and his ‘immediate surroundings’ – a figure or face in the foreground – ‘became almost transparent’. The object of his gaze was ‘really solid’ while ‘the rest becomes nebulous’. J. M. W. Turner famously sought to arrive at such equivalents in paint for the phenomena of peripheral vision.

The vague foreground of Slagheap Railway serves to lead the viewer on a journey up the hillside along tracks that carry drams loaded with slag to a mountaintop resting-place. As reference material for paintings such as Coal is Cheap at Any Price and After the Shift, Chapman engaged his friend, the Aberaeron photographer Ron Davies, to visit a colliery with him to capture – in deliberately blurred photographs – the miners as they emerge from underground. They had been working for an eight-hour shift hewing coal. Toiling in hot restricted seams, the miners, faces blackened by coal dust, were forced to use the back of their hands to clean the eyes, nose and mouth. As a result, they emerged from the cage, thought Chapman, looking like clowns. The driving force, he maintained, was creative rather than political. ‘I have no social comment to make in my paintings’, Chapman told Huw Weldon in 1961, ‘my job as an artist is to take things as they are. Providing I do my job properly, the social comment, if such a thing is needed, will come over by itself’.

By the time he staged his third solo show for the Zwemmer Gallery off Charing Cross Road in 1965, Chapman’s energetic application of paint was as important as the subject itself. ‘Gradually Chapman is becoming more painterly, his colour more subtle, and his surfaces dense with matter’, John Dalton observed in The Guardian on 11 March 1965, ‘some of his surfaces already have that scarred battlefield quality we find in Rembrandt’. Though it was received with critical acclaim, the exhibition was not a financial success and few paintings sold. Tormented by self-doubt and compelled to make a living to provide for his family, Chapman gave up painting, took on more part-time teaching in London – a challenge when faced with a commute from West Wales – made landscape studies locally, and set up in business screen printing lampshades in Aberaeron.

In 1980 he returned to the Rhondda to undertake a commission. There he discovered that his beloved coal-mining valleys had changed almost beyond recognition. All that had once been so familiar had virtually disappeared. The carcass, that neither the inhabitants nor time could fundamentally alter – the hills, the rain and the terraced houses following the contours of the mountainside – had lost none of its former appeal to him. He subsequently took on the challenge to paint the new Rhondda, inspired to reflect the changes that had taken place since that first dark, wet afternoon in 1953 which, critic Royston Lambert pointed out ‘transformed his purpose, his vision and his work’. The paintings, meanwhile, continued to focus on the relationship between the people and their environment.

When George Chapman died at his home in Aberaeron in 1993 at age 85, The Guardian, The Times, The Daily Telegraph and The Independent newspapers all featured lengthy illustrated obituaries in recognition of his achievements as a painter, printmaker and graphic designer. The BBC broadcast Sir Huw Weldon’s 1961 award-winning Monitor documentary on Chapman.

It was in 1986 that I first came to know George Chapman and was pleased to have played a small part in the revival of interest in his paintings and prints. We remained close friends. At Mike Goldmark’s request, I curated an exhibition for his Uppingham gallery and wrote the accompanying catalogue. Even today it remains the most comprehensive study of the artist and his work. Many weekends I spent in his studio, sometimes with Katie, looking at paintings, prints and drawings as well as photographs and archival materials, as he recalled his career and shared his perspectives on art and life. I subsequently staged a touring exhibition of Chapman prints and started to compile a catalogue raisonné. Though many of his plates were destroyed in the late 1960s when he used them to repair the hull of his decommissioned lifeboat Yora, those nailed to strengthen the rotten floorboards of his bedroom were rescued and printed by me.

Chapman was then still painting. A new canvas of a miner was on his easel when he died. ‘I got a fantastic shock,’ he had told Huw Weldon in 1961 about his discovery of the Rhondda Valley, ‘I realised that here I could find the material that would perhaps make me a painter at last’. As well as sustain him for the next forty years, that ‘material’ resulted in some of the most significant paintings and etchings ever to concern themselves with Wales and its industrial landscape. ‘It’s a visual history of a locality, that’s what I’m trying to do,’ he told me in February 1987, ‘a simple record of what’s down there. It’s a love affair you know’.

Robert Meyrick, Summer 2017

In a series of exhibitions and publications, Robert Meyrick explores the work of one of the most important artists of the 20th century to document the industrial face of Wales.

Publications

Robert Meyrick. George Chapman Goldmark Gallery. (Uppingham, Leicestershire: Goldmark, 1992) 48pp ISBN 1 870507 14 2

Robert Meyrick. George Chapman: The Complete Etchings 1953–1980. Gregynog Festival Exhibition No.3. Aberystwyth: School of Art, 1992) 8pp

Robert Meyrick. ‘George Chapman’. (Obituary) The Independent. 3 November 1993

Robert Meyrick. ‘George Chapman’. Uned Gelf No.7 Spring–Summer 1994, Gwynedd, pp.18–22

Robert Meyrick. ‘George Chapman 1908–1993: Printmaker’. Printmaking Today Vol.4, No.1, Spring 1995. pp.11–12

Robert Meyrick. George Chapman. Exhibition Catalogue Essay. (Saffron Walden: Fry Art Gallery, 2017) xxpp

Dear Robert, I think you have done Chapman proud so far – why not a full book now? I think the Rhondda oils are magnificent and should be more widely known, the out-of-focus ones less so.

I was toying with following up my interest in Chapman after writing extensively about the Bradfield artists, but I realise there is little left to say after your own writings on him. Well done

Malcolm Yorke

LikeLike